She had come upon the word sh’khol. She cast around for a word to translate it but there was no proper match. There were words, of course, for widow, widower, and orphan, but no noun, no adjective, for a parent who had lost a child. None in Irish, either. She looked in Russian, in French, in German, in other languages, too, but could find analogues only in Sanskrit, vilomah, and in Arabic, thakla, a mother, mathkool, a father. Still none in English.

Thirteen Ways of Looking by Colum McCann

Why is there no word in English (or most languages) for what to call a parent who has lost a child? A spouse who loses their spouse becomes a widow/widower/bereaved spouse. A child who has lost their parents becomes an orphan. Could it be there is no word for a parent who has lost a child because we don’t need one?

A parent who has lost a child is still a parent.

What should we do in the face of such deep suffering?

How do we, together, become a net strong enough to help bear the weight of such sorrow?

Time and Safety

“...trauma survivors need to experience safety before they can begin mourning traumatic losses and reconnecting with the ordinary goodness of life.”(Doehring, 2019) The “ordinary goodness of life” for these parents will be forever changed. It will take time, but we can rest in the knowledge they will eventually reconnect with goodness. We help that process by holding space and creating as much safety as we can for them, allowing the process of grief to go forward in a way that will be eventually transformed (but never completely removed).

Body-aware Practices

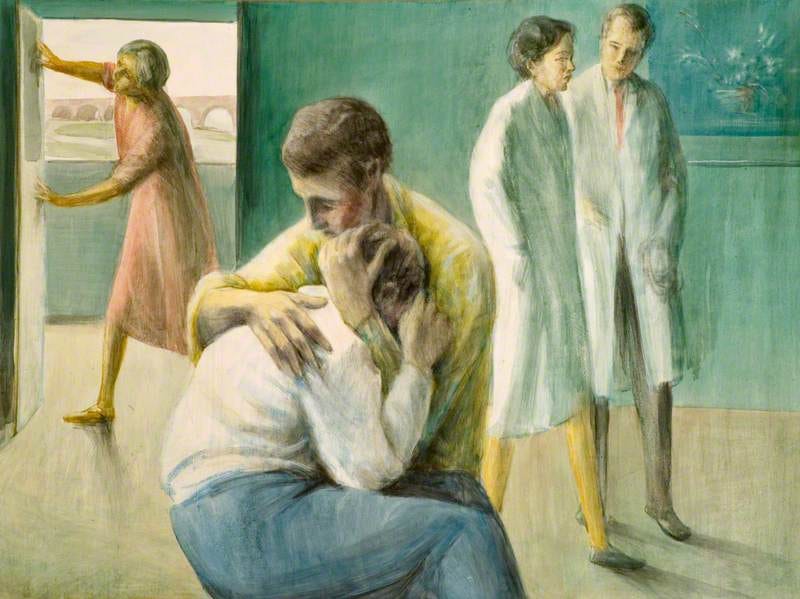

“...spiritual practices that reveal compassion, benevolence, and goodness in embodied, relational, and transcendent ways are needed in order for meanings to become flexible, integrated, and complex enough to bear the weight of suffering.”(Doehring, 2019) This is why, in all societies, our first response to unspeakable tragedy is to to bring food, to gather, to hold the weeping, to sit with them silently, to be present. It’s why there are rituals and community mourning to support those who weep. And as time goes by, it’s why walking outside, going to a yoga class, breathing meditation, listening to beautiful music, and other embodied practices are so healing.

The need to lament and share anguish

The open spiritual wound of parental grief heals slowly (and never completely). There are no words, there is no “treatment” (spiritual or otherwise) that makes this happen faster. In particular, even thinking (much less saying) things like “They are in a better place” or “God must have needed an angel” somehow conveys to mourning parents that their lamentation is somehow inappropriate. Instead, focus on sharing anguish through rituals, by listening, by telling stories, by just being together.

The healing power of stories

It is normal to struggle with what to say to a bereaved parent. But we don’t need to say anything. Our role is to “listen respectfully and be compassionately present”.(Doehring, 2015) When we listen respectfully there will be stories that will be shared… or not. When we listen respectfully we will find small ways to help, whether it is taking a sibling for a walk, reaching out to a teacher who is grieving, or putting ice cream in the freezer. When we see being compassionately present as our practice, we create space for stories, ways to help, and just sitting quietly with (or nearby).

A deep bow to my professor, Carrie Doehring, who taught me these principles.

Doehring, C. (2015). The Practice of Pastoral Care, Revised and Expanded Edition: A Postmodern Approach (Revised and Expanded edition). Westminster John Knox Press.

Doehring, C. (2019). Searching for Wholeness Amidst Traumatic Grief: The Role of Spiritual Practices that Reveal Compassion in Embodied, Relational, and Transcendent Ways. Pastoral Psychology, 68(3), 241–259.

thank you for the orientation and care, Mary. just learned of an accidental death of a 15-year old boy, son of a couple i'd met many years ago, was stopped in my tracks.

Thank you for this.